This is the sixth part of a series of articles on the relationship between jazz and comic books. Go to Part 1 , Part 2, Part 3, Part 4 or Part 05

Comics and jazz were considered marginal forms of expression for a long time. However, they reached the 21st century with the status of artistic languages and are a recurring subject of academic theses and dissertations. Despite the different points of intersection between comics and jazz, to what extent has academic recognition caused a distance between the popular origins of these languages and the transformation of an audience of readers and listeners into collectors?

The recognition of comics and jazz as artistic languages by the academic community has undeniably elevated their status and led to a deeper exploration of their cultural and historical significance. As these art forms have become the subjects of scholarly research and academic discourse, the focus has shifted towards understanding their intricate connections with society, history, and other forms of art. However, this academic recognition has also raised important questions about the potential distance it may have created between the popular origins of comics and jazz and the transformation of their respective audiences into collectors.

On the other hand, the academic recognition of comics and jazz has indeed prompted a transformation in the dynamics of their audiences. While the popular origins of these art forms were deeply rooted in mass appeal and accessibility, their academic validation has led to a reconfiguration of their audiences. The transition from casual readers and listeners to discerning collectors has been influenced by the scholarly emphasis on the artistic, cultural, and historical significance of comics and jazz.

This shift has created a nuanced layer of appreciation among the audienced of comic art and jazz, with a growing focus on preserving and owning significant works within these art forms, altering the dynamics between creators, audiences, and collectors.

So that we can better understand what is at stake in this debate, let us first turn to the concept of cultural industry, a term coined by Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer. In his 1968 article, Adorno states that the cultural industry (…) forces the union of the domains, separated for millennia, of superior art and inferior art. To the detriment of both*

This thought-provoking statement encourages us to critically examine the implications of such amalgamation, as it raises pertinent questions about the intrinsic value and purpose of art in the modern cultural sphere.

The distinction between high and low culture has been a recurring topic in discussions within the field of Cultural Studies. Raymond Williams, a prominent British popular culture critic, addressed this dichotomy, noting that the so called “high culture” tends to remain largely unchanged over time (an concrete example of this phenomenon can be observed in the realm of classical music), while popular culture plays a pivotal role in facilitating the flow of information among diverse social groups, thereby engendering the emergence of novel and dynamic cultural expressions.

The word “flow” in jazz resonates with the interconnectedness of the melodic, harmonic, and rhythmic elements, contributing to the seamless and cohesive expression of the art form, but “flow” is a fitting descriptor for the organic development of the music, as well. It aptly captures the essence of a musical movement that is essentially born in motion and displacement. This fluidity is fundamental to the improvisational nature of jazz, where musicians dynamically interact and respond to each other, creating an ever-evolving musical narrative.

Applied to comic books, “flow” is a very useful concept for understanding the integration between visual narrative and the progression of the script and highlights the intricate fusion of visual and narrative elements. It is also crucial for the reader to semiotically fill the space between frames, completing the comic narative, but the aspect of flow we would like to highlight is related to the black diaspora and its influence on both forms of expression: comics and jazz.

Flow, in this context, has to do with a dynamic exchange of cultural, artistic and linguistic elements.

The fusion of African and European musical traditions resulted in several music genres that would become identity marks, such as during the formation of choro and samba in Brazil and Argentine tango, in the 19th century (as we will see in the last segment of this series of articles) and jazz in the 20th century USA.

Likewise, the influence of the black diaspora can be seen in comic books, both from a consumption point of view, given the fact that black audiences have been prominent consumers of comic books since the 1940s, as well as when it comes to the representation of the characters. In fact, the history of the representation of black characters in comic books would be a good summary of the history of racism itself.

Since the 1990s, the black diaspora has been given new meaning in the visual arts through Afrofuturism, which presents offers a way out of the marginalization imposed by European canons. However, with regard to the representation of the biographies of jazz stars in comics, in particular, the model that usually prevails is still far from ideal, and if it manages to go beyond the dehumanization of the past, it stil reaffirms tereotypes, reinforces victimization and the cult of marginalization.

Be seeing you!

G.F.

* “Résumé über Kulturindustrie” in Theodor W. Adorno, Ohne Leitbild: Parva Aesthetica. Frankfurt am Main, Sührkamp Verlag 1968, p.60-70.

** A Vocabulary of Culture and Society. Raymond Williams. New York. Oxford University Press. 1976

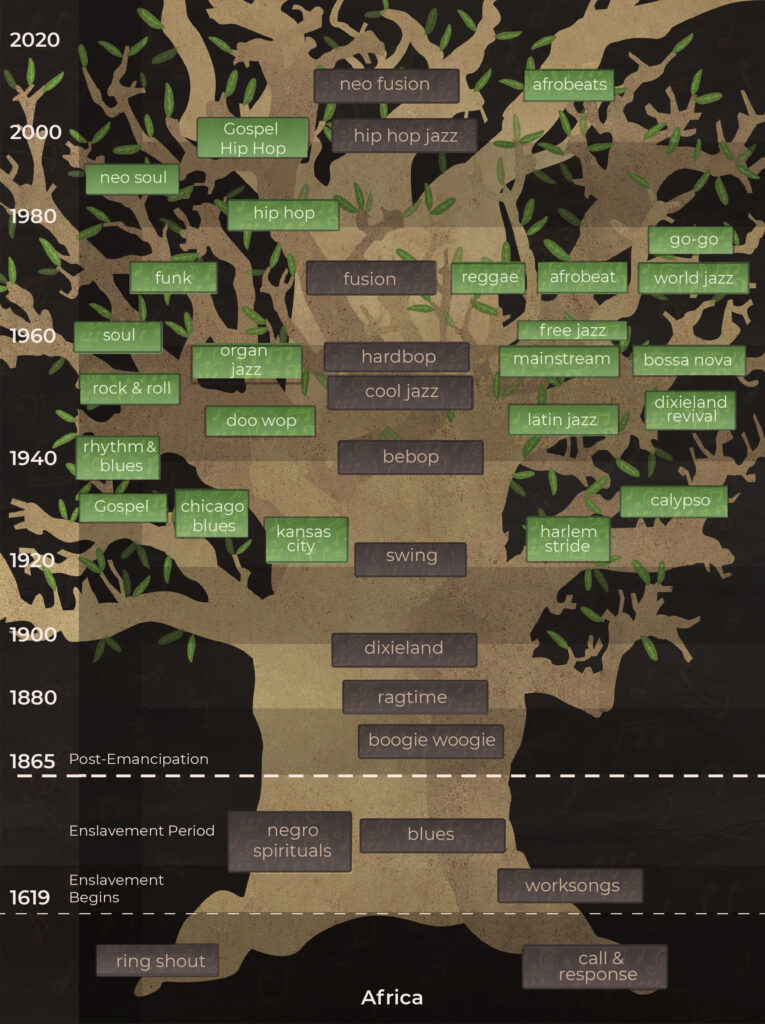

p.s. before you go, check this one version of the jazz tree. Beautiful, isn´t it?

0 Comments